A fantasy about a woman bequeathed an odd gift by a former lover who broke up with her, then died—his handwriting. Why did he do this and what does it mean?

Years before, their breakup had been ugly, drawn out, and at times brutal. Understandably, when she learned later that he had died, she felt very conflicted. Yes, the good times had been superb and there were many of them, for sure. But when things went bad between them, she literally felt like she was drowning in his cruelty, insensitivity, and rage every single day, right up till the end. Yet no matter how much she had tried to clear her thoughts of him afterward, he stayed in her mind and memory all these months later like one of those maddening translucent floaters in the eye that slide lazily around from corner to corner, blurring your vision. Eventually they move off to one side of the eye or other for a while, but never completely go away. In her honest moments she assumed he still felt bad things about her too, but now she would never know.

So it came as a complete surprise when she received a letter from a lawyer named Bellport saying she had been left something in his will. He was wealthy. In truth, part of her felt like he did owe her something for both their good and bad times over the years. She was eager to discover what it would be, although there was also a small queasy feeling in her gut in case it turned out to be something not so nice. He could be very generous, but equally vindictive or petty, depending on his mood. You never knew with him, especially at the end of their days together. Could this be delayed payback from beyond the grave?

His handwriting. He bequeathed his handwriting to her.

On hearing this, she blinked twice and gave a quick, short shake of her head as if to clear it of the something wrong that had just flown into her ear.

“What do you mean?”

The lawyer, a handsome man with a gleaming bald head and the supreme slick confidence of a Rolls-Royce salesman, smiled a little condescendingly at her before answering, “He left you his handwriting. When we were drawing up his will, he happened to mention you loved his handwriting. So—now it’s yours.” The tone of his voice said: Okay, that’s that—the topic is finished.

In response, the tone of her voice was: Are you nuts? “How can someone will their handwriting to someone else? It’s yours; it’s something you develop over the years; it’s… personal, I don’t know—physical—like fingerprints. It dies with you.”

The lawyer spoke calmly to her—a little too calmly. The quiet tone one might use when reasoning with a bratty child having a tantrum. “It can be done. Suffice it to say he did so, and now it’s yours.” He clapped his hands gently together for emphasis. “But it doesn’t mean you have to use it. You just own it. Think of it as a beautiful boat—you don’t have to use that either. You can leave it at the dock and never think about it. But it’s yours now.”

When she got home from Bellport’s office she made a cup of coffee and took it to her desk. Fittingly, she took out the gorgeous, carmine-red, Japanese lacquer fountain pen he had given her for her birthday many years before. The great irony was although she loved pens, notebooks, and everything to do with handwriting, hers was absolutely atrocious and had been all of her life. It was tiny and almost indecipherable to anyone but herself. He once said it looked like someone dipped a pigeon’s feet in ink then let it walk across the page. He was right. It had always embarrassed her, and put side to side with his precise, singular, almost calligraphic script, it was like comparing gravel to a diamond.

But his gorgeous script was hers now, supposedly. She thought it was ridiculous, impossible, perhaps even just a bad last nasty joke he was playing on her. But what the hell—she had to make sure. She may have ended up hating him back then, sometimes even being afraid of what he might do, but she had to admit that what he did well in life was often unmatched, original, and sometimes even genius. Maybe he had found an amazing way to transfer his handwriting to her.

Uncapping the pen, she pulled a small pad of white paper from the corner of her desk and, thinking for a minute, grinned when she thought of one word for what she was sort of— in a kind of way— about to do: She wrote the word plagiarize.

What came out of the pen was her handwriting, her pigeon scrawl. Not a single one of the letters was in his lovely script. No surprises there.

Smirking now, she waited a bit and then tried it again. Only this time when she began to write the word—just to make sure it was only a stupid, macabre last joke on her—what flowed onto the page were three words:

played your eyes

instead of plagiarize. All three were instantly recognizable in his beautiful script.

Recapping the pen, she carefully placed it back on the desk, although her hand trembled so the pen rattled a little when it touched down on the wood surface.

“Why? What is this?” she asked herself in a whisper, she asked the empty room around her, she asked dead him knowing he would not reply. What had he done to her? Why had he done this?

She was not a brave woman but she did a brave thing now: Against all of her instincts, she picked up the pen, uncapped it again, and started to write. She did not want to do this. At that moment she only wanted to run out of the room and away from her life because she was petrified. She looked down at her moving hand like it was the enemy.

When they were together he used to call her a “fear bakery” because too frequently she used some ongoing—usually trivial—worries, concerns, or obsessions as ingredients to bake yet another fresh hot loaf of alarm which she then devoured, making herself semi-miserable. He believed she lived in a self-created world of what ifs?’ that kept her almost constantly on edge. She had to check the stove three times to make sure it was off before she’d leave her apartment. She was the only person he’d ever known who washed or dry-cleaned clothes she’d just bought new before she’d wear them: “You never know who touched or tried them on before you.” She would eat French fries only down to the last two or three centimeters and throw the rest away. He never once saw her eat the last bit and when he’d ask her about that quirk, she looked at him silently but the expression on her face said quite clearly, “Isn’t it obvious?”

He didn’t say anything.

Neither did she.

One time they even engaged in an intense thirty-second stare-off about her pommes frites peculiarity, the end of which came when she asked, “Do you think I’m weird?”

He pursed his lips and slowly answered, “You have your quirks.”

For the third time she attempted to write the word plagiarize. And she did. It came out of the pen as she intended. Then a fourth and fifth time. But not the sixth:

played your eyes

His words, in his distinctive handwriting.

Capricious. In the days to come, she learned her inheritance from him was very capricious. It almost never interfered with her daily life—matters like writing a check or signing for packages. She had a habit of scribbling lots of notes to herself and sticking them up all over her apartment. Grocery lists, inspirational quotes, date reminders. He (and she began to refer to the event as he) almost never showed up there. She wanted to write down a line he once said when they were out to dinner. It read:

Fear is the intermission, not the play.

But when she put pen to paper what flowed out instead—in his handwriting—was:

My memory loves you; it asks about you all the time.

Was a dead man talking to her? He was, of course, but why, and what did he want?

She had never believed in life after death. Interestingly, he didn’t either, the few times they had talked about it. Neither of them was interested in the subject. Both felt that when you’re done you’re done and the only question that needed answering beforehand was how you wanted your body disposed of afterward. He joked about having his flown to Nepal or Tibet, where he could have a “sky burial.” There they lay your remains out on a rock and vultures feast on them. She didn’t think this was funny but these days she wondered if he had actually done it and that was the cause of this… thing happening to her right now.

There was obviously no one she could talk to about it without their thinking she was mad. So days went by and every time she needed to write something her stomach and lips tightened, not knowing what was about to happen.

One morning it came to her: She would try conversing with him, or it, or whatever was using his handwriting to disturb her life. She used a pencil because she thought it would be better, more neutral, than using his pen. On a yellow lined pad, she wrote at the top:

What do you want?

It came out in her familiar ugly scrawl, which was a positive sign. She waited, but both her hand and mind stayed still. Neither of them had anything to say. She tried again and wrote:

Please tell me what you want. This is driving me crazy.

Nothing. He would not answer. Her hand would not move no matter how much she willed it to.

Weeks passed and slowly she learned to accept his bequest. Truth be told, writing in his beautiful script became a daily joy. Whether it was her choice or not, eventually her handwriting morphed completely into his. Nevermore did any inked pigeon feet walk across her pages. If it was his gift then she chose to use it. If sometimes he sent little mysterious— usually cryptic—messages to her via that gift, the trade-off was more than fair.

She had to change a few things in her life to make it fit. Her bank, insurance, and credit card companies were all notified that she had changed her signature. At work a few people noticed the transformation because she was in the habit of hand-writing informal notes to colleagues rather than sending emails, especially now writing had become such a pleasure for her. When asked about this, she said she had been taking an online calligraphy course. To her delight, people complimented her, saying again and again how lovely her handwriting had become.

One summer night several months later, a violent thunderstorm swept through the city, scaring all the dogs and burning up the sky in what looked like almost continuous threads of mad lightning. Her father used to call such storms real rock and rollers, and this one certainly was. The phrase and the memory of her father saying it was the last thing she thought of before falling asleep while the storm rocked and rolled the night world outside her window.

An hour and a half later (at some point she glanced at the clock next to the bed), she woke after a particularly ferocious crack of thunder bit all the way down through her sleep. It took a while before she rose to full consciousness because when she slept, she slept deep, and people had always said rousing her was a real chore. When her eyes came into clear focus, the first thing she saw was a very strange sight. For long seconds it didn’t really register: Her right arm was extended straight out in front of her toward the ceiling. As she blearily watched, her hand moved up and down, left and right, all on its own, in a familiar way she gradually recognized was as if it were writing.

“What the hell…” Fully awake now, she snatched the arm back down to her chest and cradled it there as if she’d hurt it. The arm surrendered with no resistance. For dramatic emphasis, another great crack and boom of thunder rattled her world. She flinched, although thunder didn’t normally bother her at all.

Raising her hand to her eyes, she looked at it as if it were something that didn’t belong to her. Why was it up in the air doing a weird writing thing while she slept? Was it something to do with a dream she was having but couldn’t remember now she was awake? Maybe it was. In the past, lovers had complained that she often spoke, moved around a lot, and even flailed her arms in her sleep when a dream was especially bad or vivid. She even slapped one guy, who took it to be a sign they were in trouble as a couple if she was smacking him in her sleep.

One cold fall day she took a nap on the couch under a thin blanket. When she woke, her arm was straight up in the air, her hand moving rapidly in a familiar way.

Again the next week. Then once again a few days after that. It didn’t scare her but it disturbed her, for sure, as one would imagine such a thing would upset anyone. It seemed like her hand and arm had taken on a life of their own while she was asleep. What they were doing (or writing) in this other life was a mystery. It made her wonder if it might be a good idea to go see a neurologist.

She met a new man. How it happened was sort of magical: On a windy day, she was at an outdoor newsstand buying a magazine. She took a five-dollar bill out of her wallet to pay. The wind gusted and blew it out of her hand. Funnily enough, it flew through the air and landed flat on the face of a man who was walking by. Without a moment’s hesitation and with absolute coolness, he nonchalantly peeled the bill off his cheek, stopped to hand it to her, ducked his head in a quick bow, smiled beautifully, and then kept moving. She couldn’t believe what had just happened and burst out laughing. But still, she managed to call out, Wait! before he disappeared down the street. They talked. He was great. They kept talking until he asked her if she’d like to move out of the wind and get a coffee. The beginning. He wasn’t a dreamboat, the man she had been waiting for her whole life, but he was pretty damn great. He seemed to be as excited about the relationship as she was, and that thrilled her even more.

To her great embarrassment, the first time they spent the night together, she did the writing thing in her sleep. She was awakened by something pulling gently on her arm. Opening her eyes, she looked up and saw he was pulling her arm from its skywriting position. The word she’d started thinking of it as whenever it happened—skywriting. She was mortified that he had seen her doing it. Especially tonight, when everything had been going perfectly right up till the moment they fell asleep in each other’s arms. But now he’d think she did crazy things like write on the ceiling when she was fast asleep. Naturally, he would probably wonder what other kind of wacko behavior she had in her dark closet.

He thought it was very cool. Really—he did. When she tried to explain that she was helpless to stop the gesture, he shook his head and said he thought it was fascinating. Maybe her subconscious was writing a book while she slept—a novel or a memoir. “That’s a book I’d want to read!” he joked, and she could tell it was not meant in any mean way.

She was rueful, and sort of whispered, “Or maybe it’s a horror novel.”

He wouldn’t accept it. He must have talked for ten minutes in the dark in the middle of their first night together with great enthusiasm about what her skywriting might mean. As he spoke and smiled and spun his thoughts, she stared at him, at his nice, open face, and fell for him ten times more.

After that night, she almost never did skywriting again when they were together. She felt relieved, no matter how accepting he was about it. Who does such things in their sleep? She had already been told by her last lover that she had her “quirks,” and this new one was a doozy no matter how you looked at it.

She assumed she didn’t do it around the new man because he had some kind of calming effect on both her conscious and unconscious minds. It certainly felt like it. She slept better when they were together; she was much happier in general since meeting him. One afternoon they were watching an old Preston Sturges film on TV. During a commercial, he killed the sound and asked what was on her bucket list. What would she like to do or see or possess before she died? He was serious—she could tell he really wanted to know. It was one of his most endearing qualities—he wanted to know her better than any man she’d ever been with. He wanted to know about her past, her dreams, hopes, fears, the things about herself she felt pride in.

Without hesitating, which was normally not her way of doing things because she was careful and circumspect, she said immediately, “Nothing. I realized the other day there is nothing more I want in my life than what I have right now.” She started to tear up. She turned her head to one side and wiped her eye with a thumb. He took her hand. She shook her head and smiled. “Part of it is because of you, part is because things are just good in my life right now. Not perfect and not Oz or anything, but good. Do you know what I mean? I don’t think I’ve ever felt like this. Before, there was always something in the way of happiness, or something that needed correcting, or I felt that life would be better if it were just a little bit more this way or that. But I don’t feel any of those things lately. It feels like life is my friend these days. ”

It stayed her friend for a long time afterward. The skywriting continued, but she grew sort of used to it. If she woke in the middle of the night and saw her arm up there in the air doing its writing thing, she just pulled it gently back down like you’d rearrange an infant’s outstretched arm as it slept in its cradle.

She was given a raise at her job. Her new man took her along on a business trip to Dublin, where one night, in a century-old pub near the river, two tall men with ginger hair stood up and sang an a cappella version of “On Raglan Road” so sad, mysterious and… wondrous that she knew instantly this was one of the greatest, most perfect moments of her life. Too often we miss the full greatness of these moments even when we’re right in the middle of living them. Why? Because we’re distracted by the dull hum and buzz of our every day, the annoying white noise and gigabytes of trivia filling the hard drive of our thoughts. Sadly, we race past the rare perfect times half attentively and too fast, seeing them, experiencing them, but not really. Like looking out the window of a speeding train at an amazing medieval castle perched on a cliff. Only later do we grasp what we’d seen and wish like hell we’d at least taken a picture.

She didn’t see it at first when she got up at three a.m. one morning to go to the toilet. She was half awake, sleepy eyed, looking toward the bathroom. But when she returned and had gotten into bed, when she rolled onto her back, there it was: directly in the air above her, an arm’s length away, was writing. Lines of words in vivid silver lettering above the bed; words written in her/his singular script. They hung there suspended, beautiful in the dark like glittering silver tinsel on a Christmas tree.

Slowly, she raised a hesitant arm and tried to touch them. Her fingers went right through the letters, but they did not disappear. She waved a hand back and forth across the words, across the sentences, across the air above her. Nothing—they did not move or go away.

What did they say? She couldn’t tell—it was a language she didn’t know or recognize. It was all eerie, frightening but also beautiful to see. Thin, silver-lettered sentences floating in the dark above in her own handwriting, his handwriting, the handwriting he had given her and she had made her own. What crossed her mind as she stared at it were the first words she’d ever written in his handwriting: played your eyes instead of plagiarize.

She reached over to a table next to the bed for the pad and pen she kept there alongside whatever book she was reading at the time. She loved copying down lines or passages that stuck out or had meaning to her. Of course she had a notebook specifically for collected quotes, now all written in her lovely new script. Propping herself up on one elbow, she copied the mysterious silver words onto the pad. She didn’t know what they meant but maybe in time she could find someone who did.

Or…

Excited by an idea, she got out of bed again and after a last glance at the words still hanging in the air, she left the room and walked a few steps over to her small study. Switching on the computer there, she waited for it to boot up. Once it did, she went to a universal language translation site, typed in the words written on the pad, told the site to “detect language” and then translate them into English.

The doorbell rang. It was three o’clock in the morning. Seconds later it rang again. Rising from the chair in front of the computer without having seen the translation, she walked to the front door, pausing only to pick up the gray aluminum baseball bat she kept leaning against a nearby wall for just such an occasion, not that she’d ever had to use it before now.

She stood up against the door, both hands on the bat, and looked through the peephole out into the hallway. Standing there, immaculately dressed in a blue pinstripe suit, white shirt, and dark tie (at three o’clock in the morning) was the lawyer, Bellport.

As if he knew exactly when she was looking, he held up a brown paper bag next to his face and said cheerily, “I brought brownies from Bouchon! I know you love ’em!”

Confused and totally hyped up by what she thought was a threat seconds ago, she leaned the bat against a wall, undid the locks, and opened the door.

“What are you doing here?”

“Can I come in? I know it’s late but we have things to discuss. If you want, we can do it out here, but—”

Hesitantly, unhappily, she stepped aside and gestured for him to enter. She pointed him down the hall toward the living room. He moved and she followed. Glancing at the baseball bat, she thought about taking it along just in case, but shook her head.

Bellport plunked down on her small couch and opened the bag. Bringing it up to his face, he inhaled deeply. He shook his head at the lusciousness of the aroma inside. Next he took out two of the obscenely expensive brownies and placed them in the center of a lime green cloth napkin, also from inside the bag. He gestured for her to have one but she said no. He shrugged and took one. Holding an open hand under his mouth to catch any crumbs, he took a big bite and closed his eyes while chewing. From the ecstatic look on his face, the man knew how to enjoy a brownie.

“Why are you here?” In spite of her uneasiness, she could feel fatigue streaming back into her like honey poured into a bowl. She needed to be sharp and alert. But for God’s sake—it was the middle of the night and the last hour had been one bizarreness after another, topped off now by this lawyer eating brownies on her couch at three a.m.

He held up a finger for her to wait a sec while he swallowed the last bite. On finishing, he shook his head at its scrumptiousness, brushed off his hands, and smiled.

“It’s part of the history of the future.”

“What is?” She sat down on the far end of the couch.

“The writing above your bed; the writing you’ve been doing in your sleep the last few months. It’s all part of the history of the human future. You couldn’t understand any of the words you’d written because none of them had happened yet. As soon as they do, you’ll recognize them. But this is not important now.”

“Are you going to eat this?” He pointed at the second brownie. She shook her head. He picked it up, smelled it, and took a bite. A few crumbs fell off his lip. He touched his mouth in embarrassment. “Sorry. But it just tastes so good.”

“I’ve been doing this for months? Writing silver words in my sleep?”

“Yes, the moment you chose to change your handwriting permanently to his. Remember when we first met I said you didn’t have to use it at all? But once you voluntarily made the change, you became a historian. It’s what happens when you choose the handwriting. This is how it works.”

“How what works?”

“The process. Mankind creates its future by its actions in the present. What you do today will usually determine what you do or what happens to you tomorrow. Think of it on a giant scale and you get an idea of the amount of data that must be recorded before the future is determined. Historians collect and record the data. You’re one of them now.”

“But I don’t do anything. My life isn’t special or interesting and I don’t even know what I’m writing in my sleep. So how does any of it help to plot the human future?” Her voice was all sarcasm.

Bellport raised his hand as if to get her full attention. “Remember when you were in school and the science teacher said humans only use a small portion of our brains to live? Well, very much simplified, what you’re writing in your sleep are the observations of all the things your brain is registering, all the time. Now multiply it by millions: Millions of historians recording what they have experienced for the past two hundred thousand years. They don’t need every person’s history—just a cross section of humanity is enough. Part of the knowledge you’ve accumulated just by living is what will happen to you in the future. Yes, somewhere in your mind you know what will happen to you tomorrow and for the rest of your life. Some of it is what you wrote tonight and why you can’t read it yet. When all of the human brain is working and producing information, it’s a wondrous machine. It knows almost no limits.”

She swallowed her incredulity and doubts for a moment and, going along with what he’d just said, asked the obvious question. “What do they do with this information we give them?”

“Sift through, refine it, and cull what they consider unnecessary things. Ultimately use what they keep to design the future of humanity. From what I understand, they put the pieces together like an ever-expanding jigsaw puzzle.”

She crossed her arms, unconvinced. “If they’re so powerful, why do we need to write it? Why can’t they just read our minds?”

“Because writing is a human invention and how we convey our experience to each other. Through writing and speaking. There are some historians—”

She cut him off. “Who probably talk in their sleep without knowing what they’re saying.”

He popped the rest of the brownie into his mouth and nodded.

“Who are they?”

If she expected him to say something stunning like God or aliens, she was disappointed. He shook his head and smiled. “I have no idea. The only thing I’ve been told is that the answer is so complex it’s like string theory multiplied by a hundred.”

She stood up, annoyed and tired and scared and other ugly things. Things she couldn’t put a finger on if you asked her to explain, but she didn’t like feeling them, not at all. These feelings were all roiling around inside her like ten hamsters running madly inside their wheels. “How do I know any of this is true? How do I know it’s not all bullshit?”

Bellport answered in a calm voice. “Fair question. Go back into your bedroom and take a look. I’ll wait here.”

She had never been afraid to go into her bedroom—quite the opposite. It was her sanctuary, her fortress of solitude against the world when it turned nasty on her. But she was afraid now.

The writing above the bed was still there. The beautiful silver letters spelling out some enigmatic who knows what.

No, wait, that wasn’t true.

Closer to the bed she realized she now understood several of the words she’d written there. Not many, but a few. She saw brownie and Bellport and… marriage. Reaching out to touch them, her fingers passed right through… She touched marriage, then closed her hand around it, as if trying to catch a firefly. When she opened it again, the word she had thought about and sometimes hoped for and sometimes cried about over the years sat unmoving in the middle of her hand.

“How many?”

She turned and saw Bellport standing in the doorway.

“How many what?”

“How many words do you understand there now?”

“Three.”

“It’s a beginning.”

“One of them is ‘marriage.’” She didn’t know if the word came out of her mouth surprised or shy.

“Is that good? Do you want it?” His voice was kind.

“Yes, I think so. But why am I seeing it now when, from what you say, I’ve been doing this since I changed to his handwriting?”

“Because it’s the first time you see the words. And now you recognized some of what you’ve written.”

“But I didn’t recognize any of them when I first saw them before.”

He slid his hands into his pockets. “This is why I came. Because just actually seeing them for the first time is the formal beginning of the process for you. The next question is, do you want to continue? You’re only asked once and the decision is final. So think carefully before you answer.”

“The more I do this writing for the future, will I be able to recognize more of the words? Will I be able to see more of my own future?”

“Depends on the person. Your friend was very aware of when he was going to die long before he did. He said it was one of the reasons why he broke up with you—to spare you having to be around him at the end. It’s also why he willed the handwriting to you when he did. It must be formally passed on whether it’s the handwriting or the voice.”

She couldn’t resist. “Even cavemen passed it on two hundred thousand years ago?”

Bellport smiled. “You’ve seen the cave paintings at Lascaux. Those guys were very adept at communicating. So yes, even they had their ways of passing it on.

“If you accept, you’re required to formally pass it on too, at some point. But remember, knowing your future is not always a good thing. It can stain a life. Or ruin it. Just so you know—he loved you very much. He said you were the only person he had ever completely trusted. It may sound trite, but he said very passionately he believed in you. That’s why he wanted you to have the handwriting—so you could decide if you wanted to use it. Obviously there are many other people doing this, many people contributing. But if you choose to do it too, you’ll be part of shaping humanity’s future, and that is no small thing.”

“Mr. Bellport, who are you?”

“Just the messenger. No more and no less.”

Looking at him, thinking about all of this, she remembered the first time she had written like the dead man. She tried to write the word plagiarize but instead wrote played your eyes. What did it mean? Was it a message from him in death? Or from some secret part of her own brain telling her to be careful—don’t get played. Or maybe it was saying don’t plagiarize, this is not what you should be doing. Or maybe—

She turned back to the words, so silver and beautifully written, floating in the air. Running a finger beneath one of the sentences, she knew whatever she decided now would change everything.

And then, in the midst of this mind-flurry of thoughts blowing every which way, it suddenly came and hit her hard: He had loved her. He had really loved her, and much of what he had done to drive her away was not because of cruelty but because he wanted to spare her even greater pain and loss when he grew sicker. And when he was gone there was this final gift to her, the handwriting. The astonishing gift would enable her to know her future even though he knew he would not be part of it.

It had always been such an ugly mystery to her—why he had been so awful at the end of their relationship. Now she knew why. The mystery was solved in the most beautiful, heartbreaking way possible. He had pushed her away when he needed her most. She hated him for doing it, now she knew the truth. At the same time she also loved him like she had never loved him before—for exactly the same reason. The mystery was solved, and with it came her answer.

She looked at Bellport and said, “No. I don’t want it.”

He said nothing, waiting for her to continue.

“If I know what’s going to happen to me, then there’s no mystery in life. Mystery, just in general, is one of the greatest things we’ll ever experience—having mysteries in our lives and now and then solving them. Sometimes solutions to our mysteries suck, but sometimes they’re so incredibly beautiful…

“Let someone else write our future history, Mr. Bellport. I want my life to be full of mysteries right up until the end.”

He bowed his head, smiled, and reached into a pocket for a folded piece of paper. Handing it to her, he said, “He thought you would say no. If you did, he wanted me to give you this before I left. I’ll let myself out.”

When the lawyer was gone, she unfolded the paper. On it, in that beautiful, beautiful script, were the complete lyrics to the song “On Raglan Road.” At the bottom of the paper he had written, “I knew this much about your future but no more. Travel well without knowing what’s next. I wish I had.”

Copyright © 2018 by Jonathan Carroll

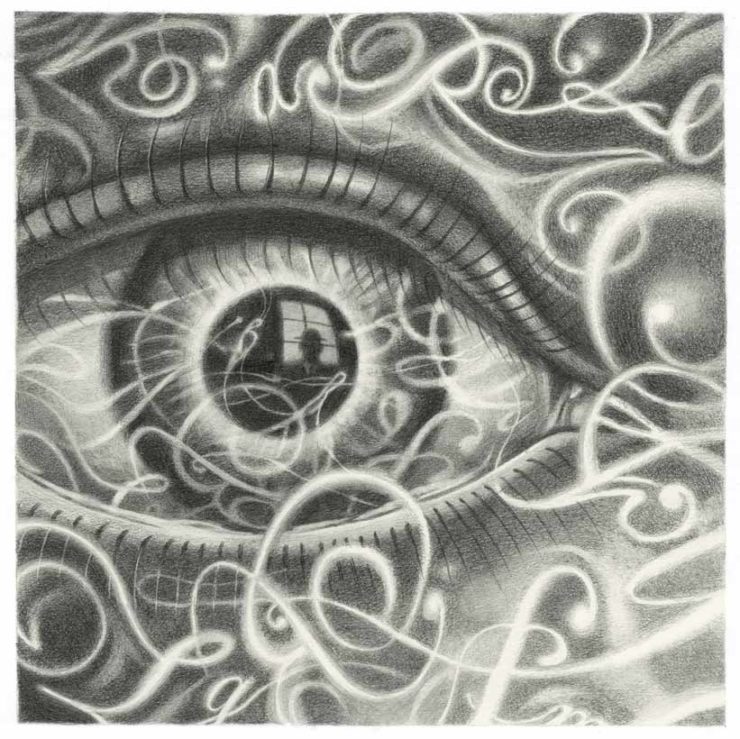

Art copyright © 2018 by Armando Veve

Buy the Book

Played Your Eyes

I always enjoy Jonathan Carroll’s writing, and this was lovely. It brought Tuck Everlasting to mind, perhaps because not all of us want to know what happens next.

I rarely comment, but that was stunning. To the author: thank you.

Beautiful. Thank you.

As someone who also has atrocious handwriting, this story really spoke to me.

This story has calmed my heart and rendered me speechless in othe best way. It’s messsage is truly one of life’s rare and simple gifts that could not have been more perfectly delivered. Thank you so very much, Mr. Carroll.

Thank you.

Thank you so very much Mr!

Gah, not the old “ten percent of your brain” myth! Sorry, that threw me completely out of the story. Still, nice to see a Jonathan Carroll story where people make good choices and get a happy ending for once.

@9: For me, it was the “Oh, he treated me badly because he really wuved me! How beautiful!” that made me throw up my hands – “I shall withhold information and ignore your right to make your own decisions about our relationship For Your Own Good”, paired with “Let me bequeath you a creepy gift – informed consent? Who dat?” Run fast and run far, girl!

The story is lovely, but the ten percent of your brain is bullshit.

@10, there are few things more infuriating than a lover deciding unilaterally what’s best for you but in this case it’s better than thinking ‘he never loved me’.

As much as I agree with some of the comments, I really enjoyed this. Thank you.

I agree with the discomfort some readers had with the idea that bad behavior = true love. I was also frustrated by the mysterious handwriting and the silvery skywriting, but those seemed gentle enough plot devices to get us to what really interested me – the woman’s growth, how she let herself feel and be happy. The lawyer’s final revelations were a harder hurdle – a mysterious mechanism and cabal to write human history and future felt convoluted & unnecessary. Despite this, as I read the former lover’s final note, I felt a long shiver. Something beautiful and vital came through, poignancy about the beauty of exquisitely lived moments, blunting the pain of hurtling blindly into our futures. I’m glad I read it.